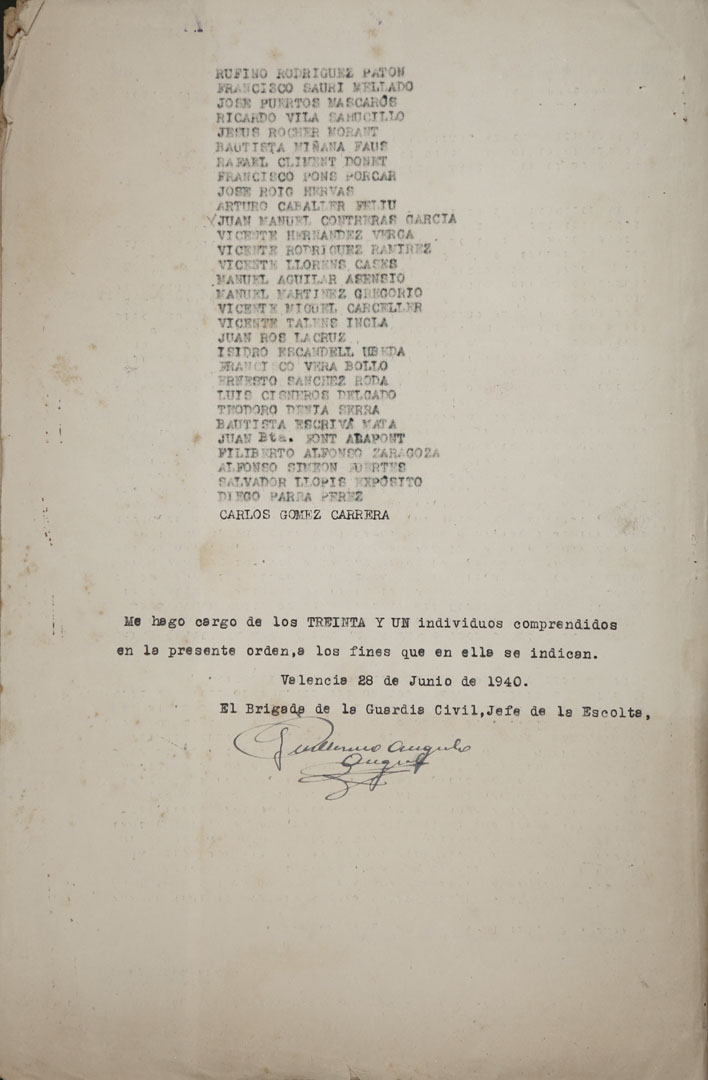

Castelló 162

València 373

Alacant 77

Totals 612

* Figures updated in winter 2025 after the latest research by Arqueoantro.

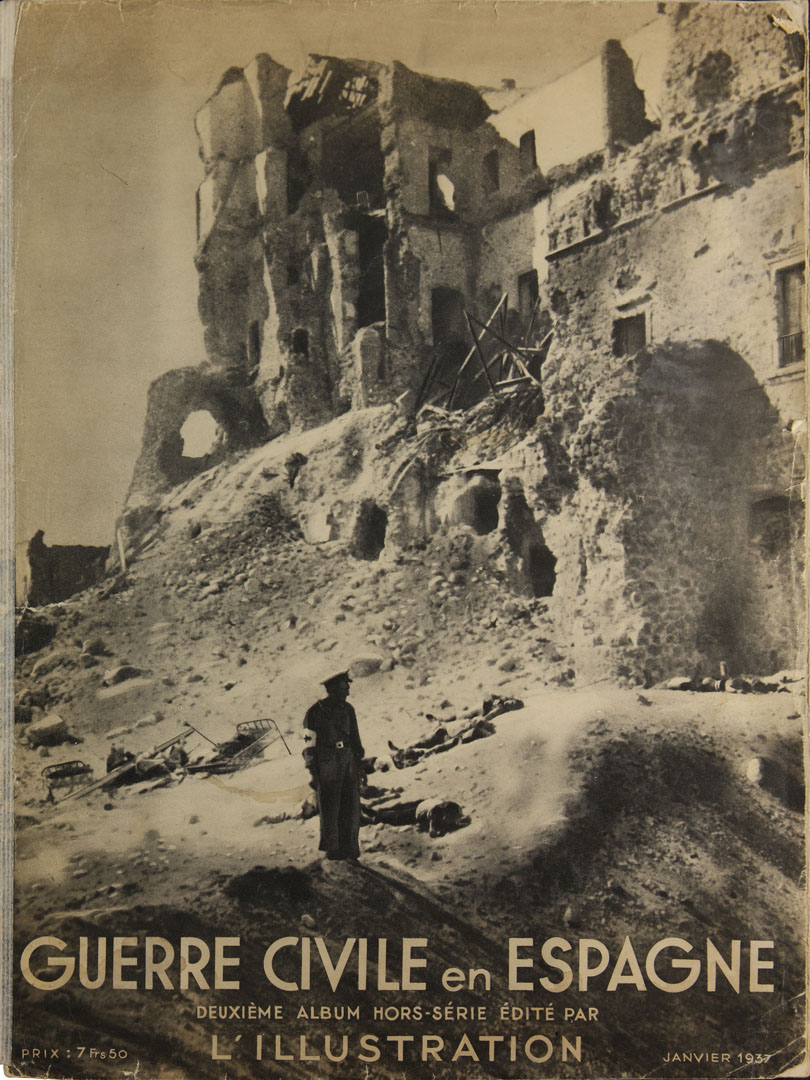

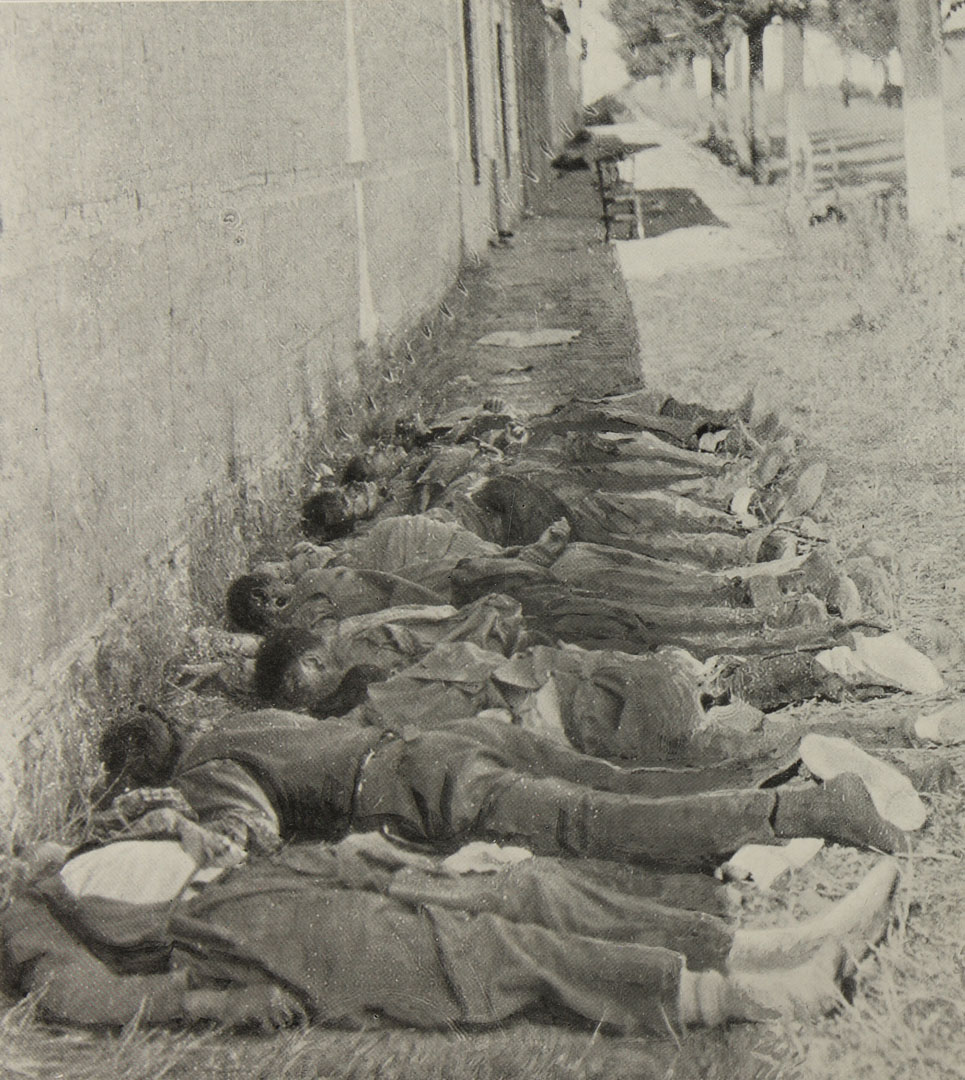

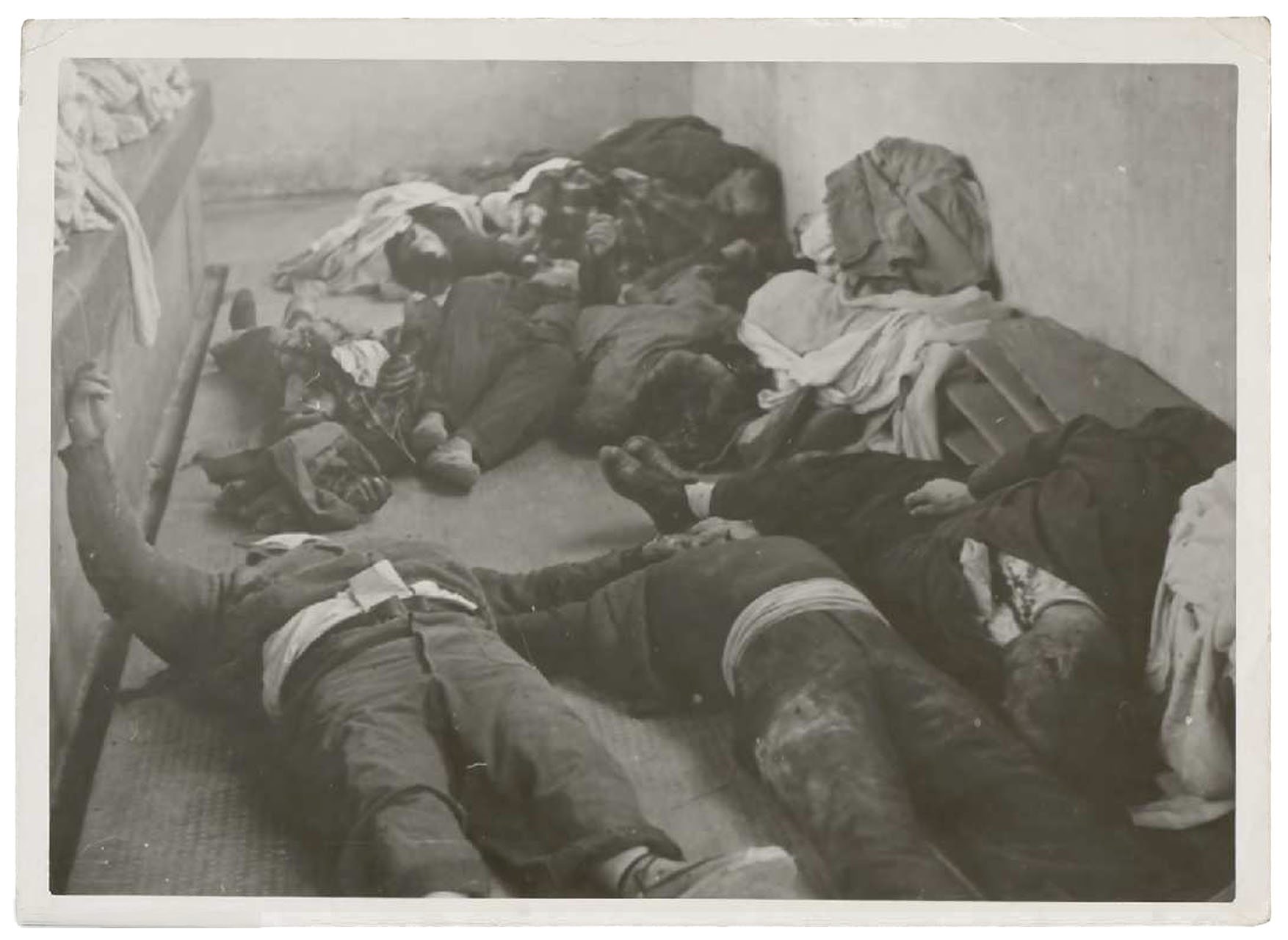

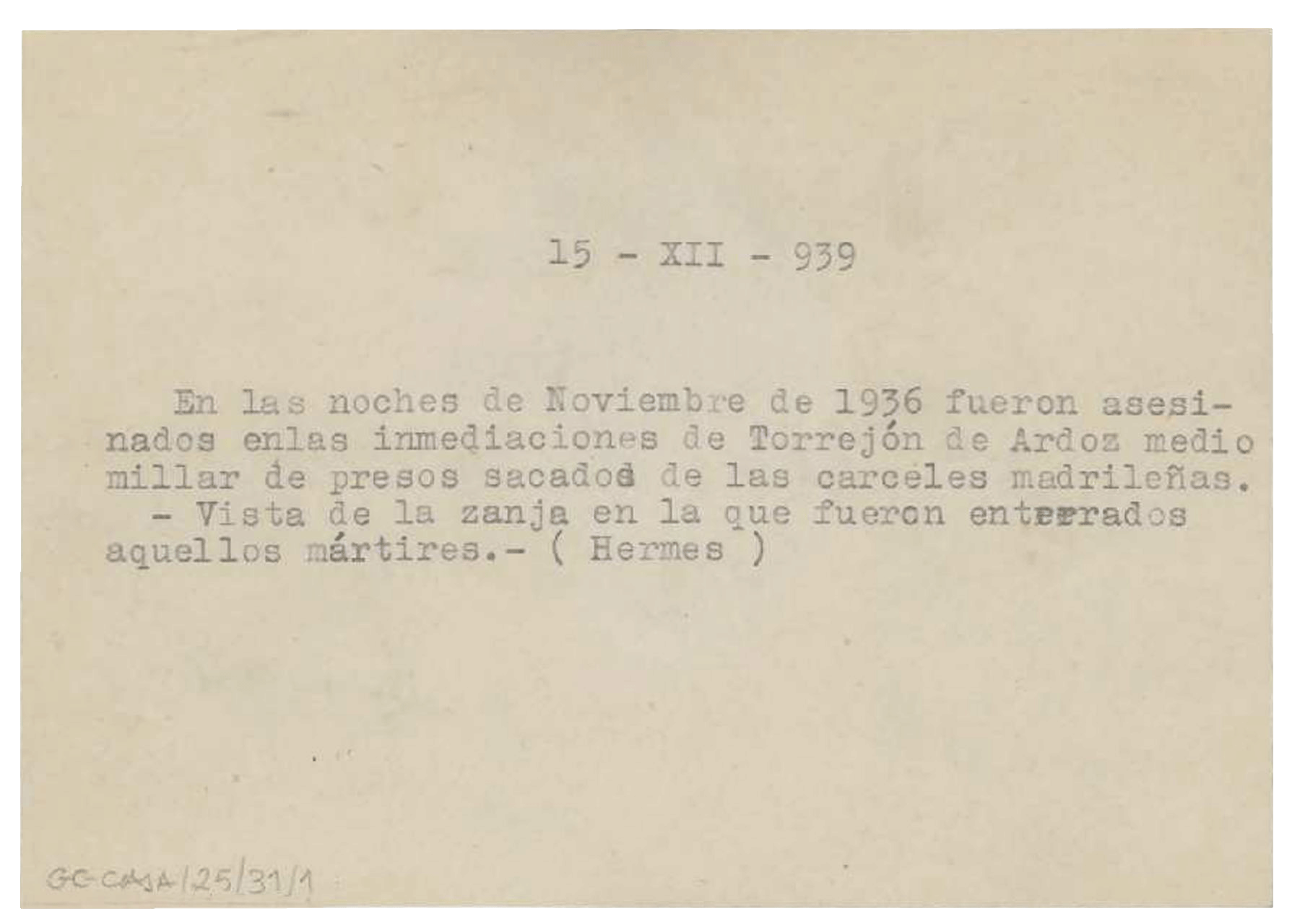

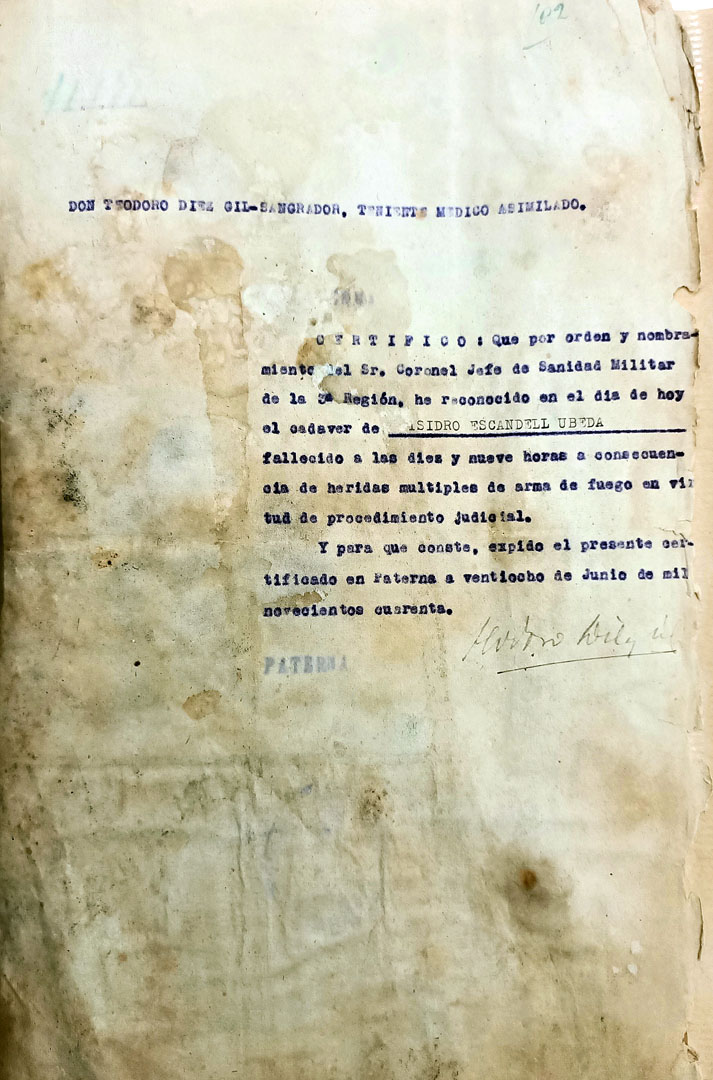

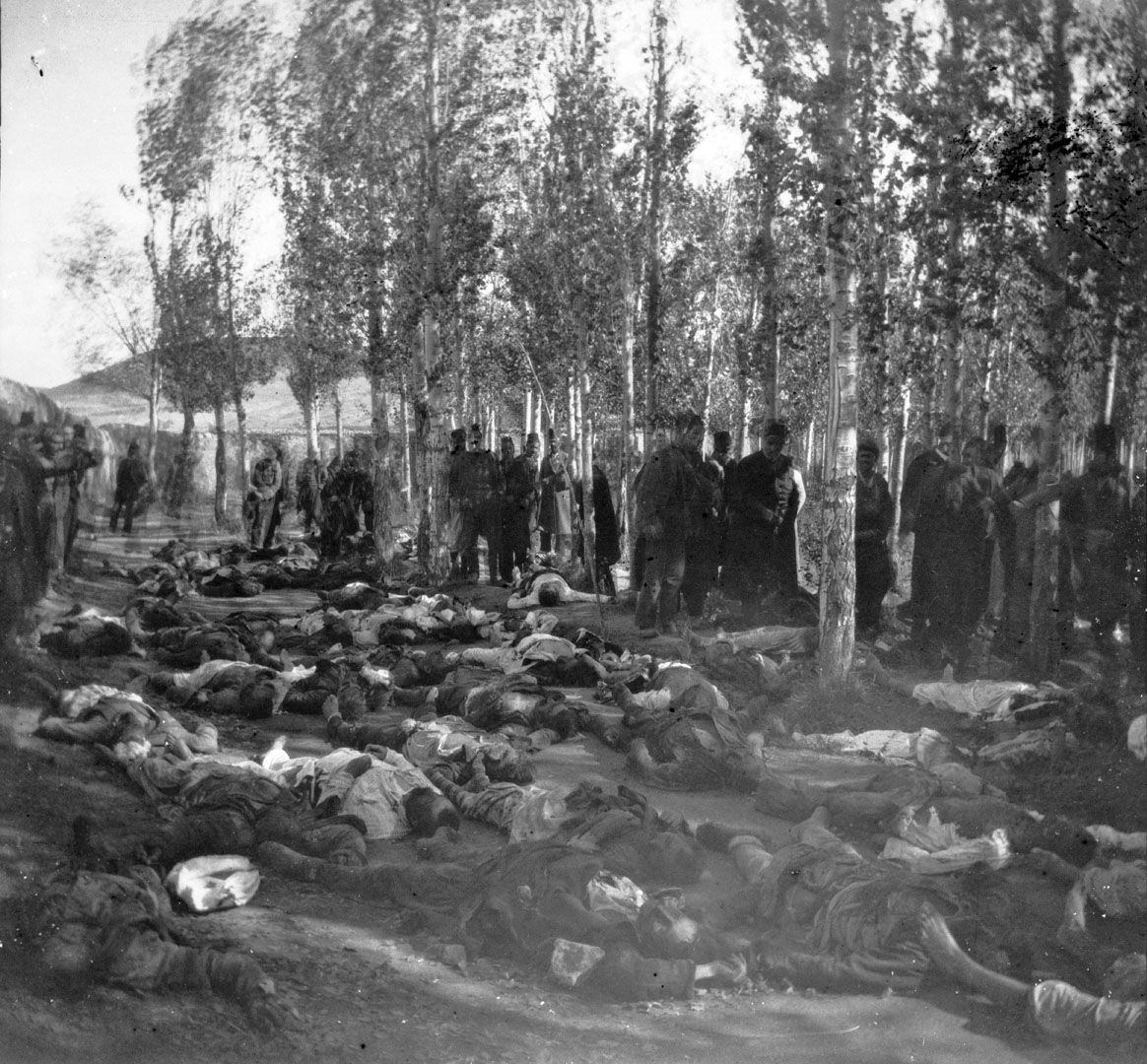

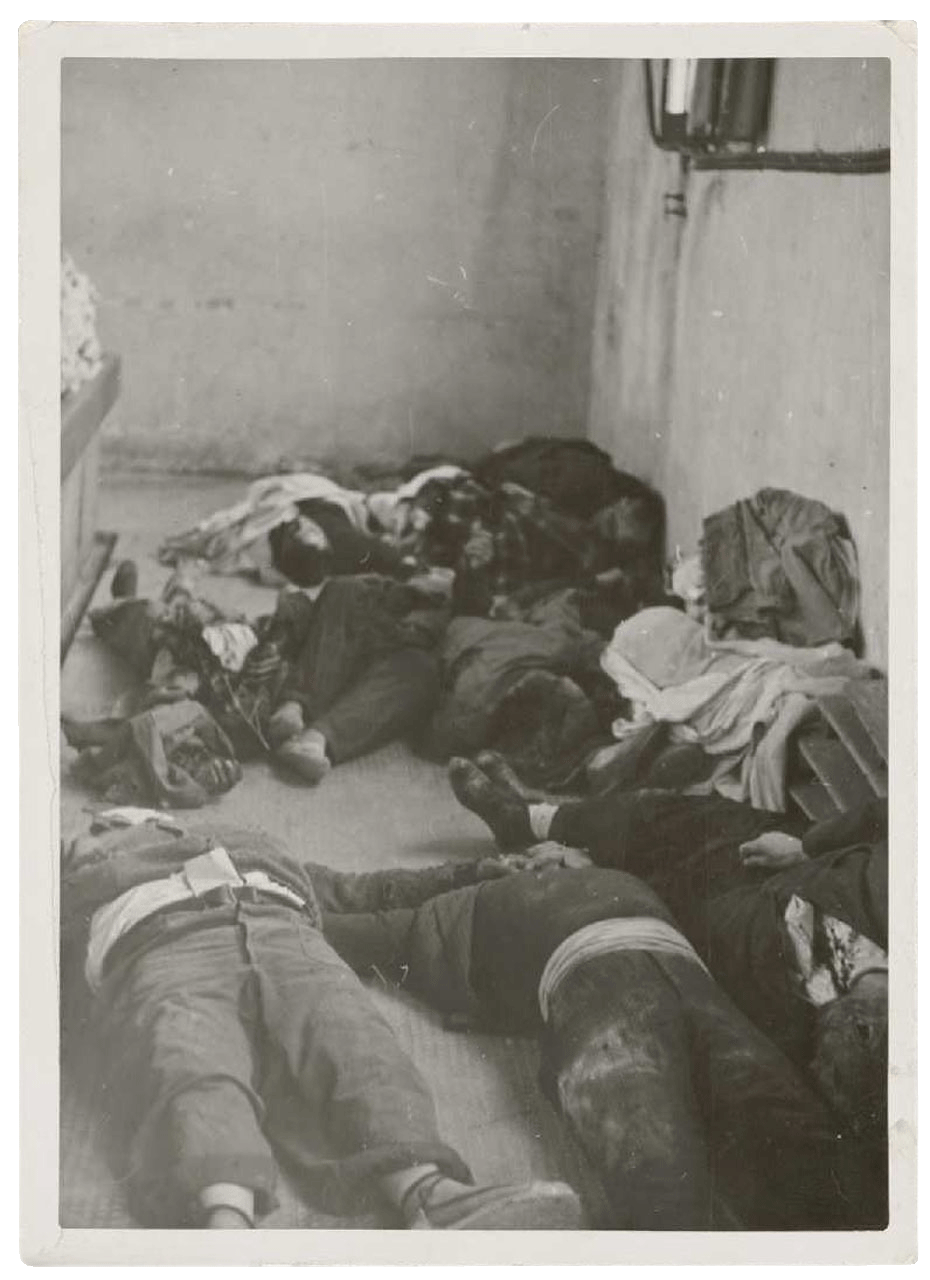

Paterna also witnessed executions by the Republican rearguard.

Similarities?

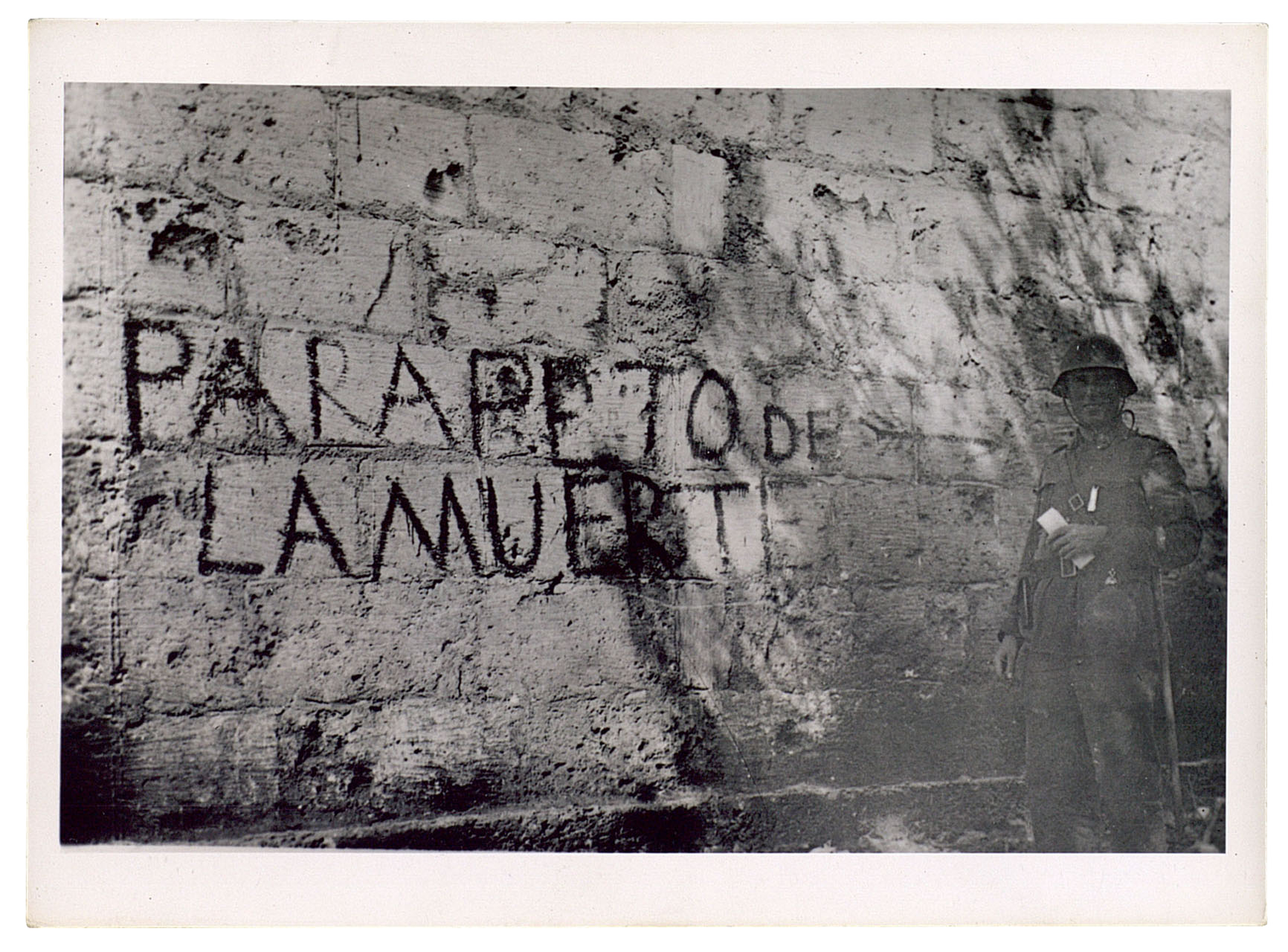

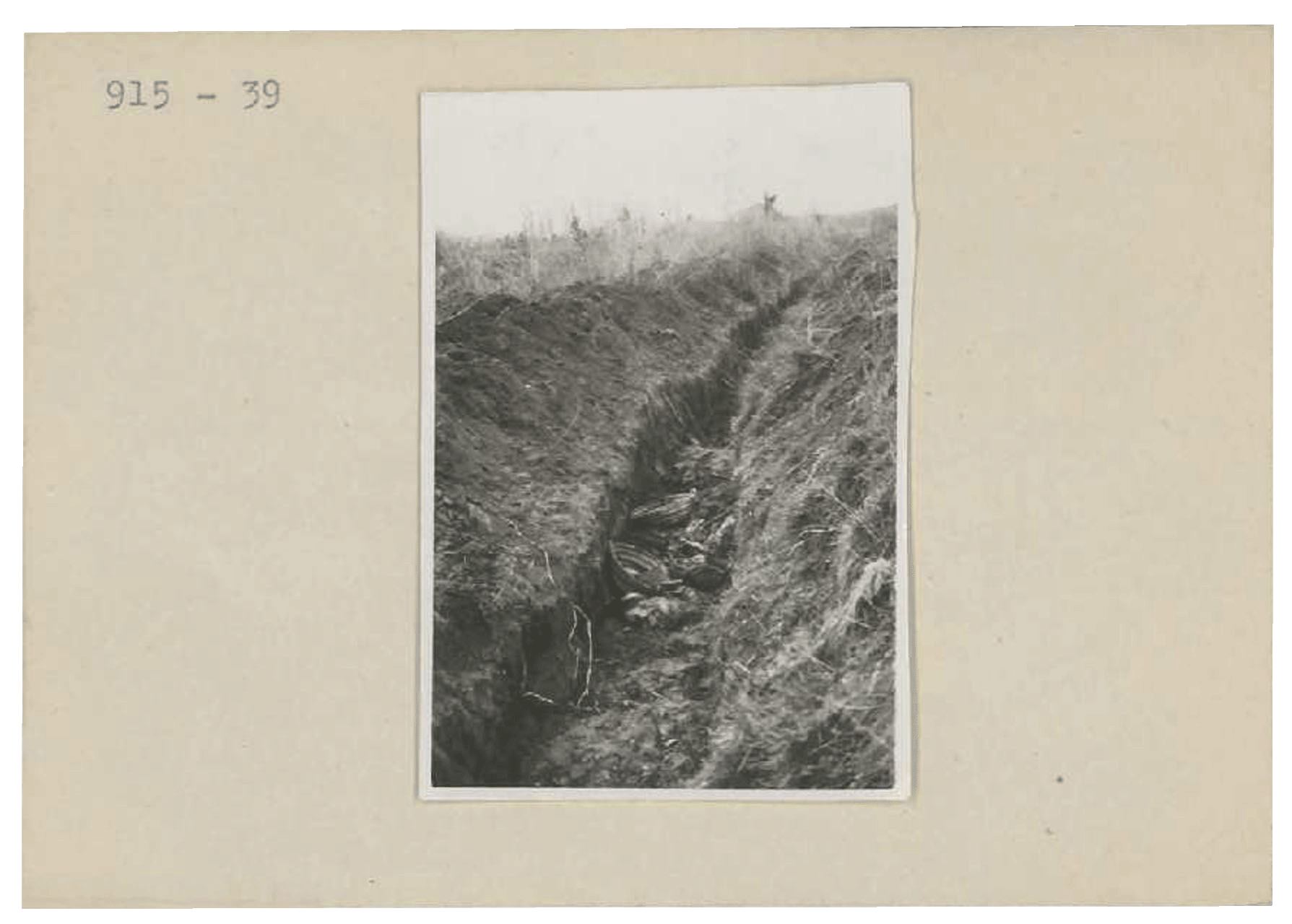

During the initial months of the war (roughly between mid-1936 and early 1937), the chaos led to 450 executions. Buried in Paterna and the Municipal Cemetery of Valencia. Without trials or the right to a defence

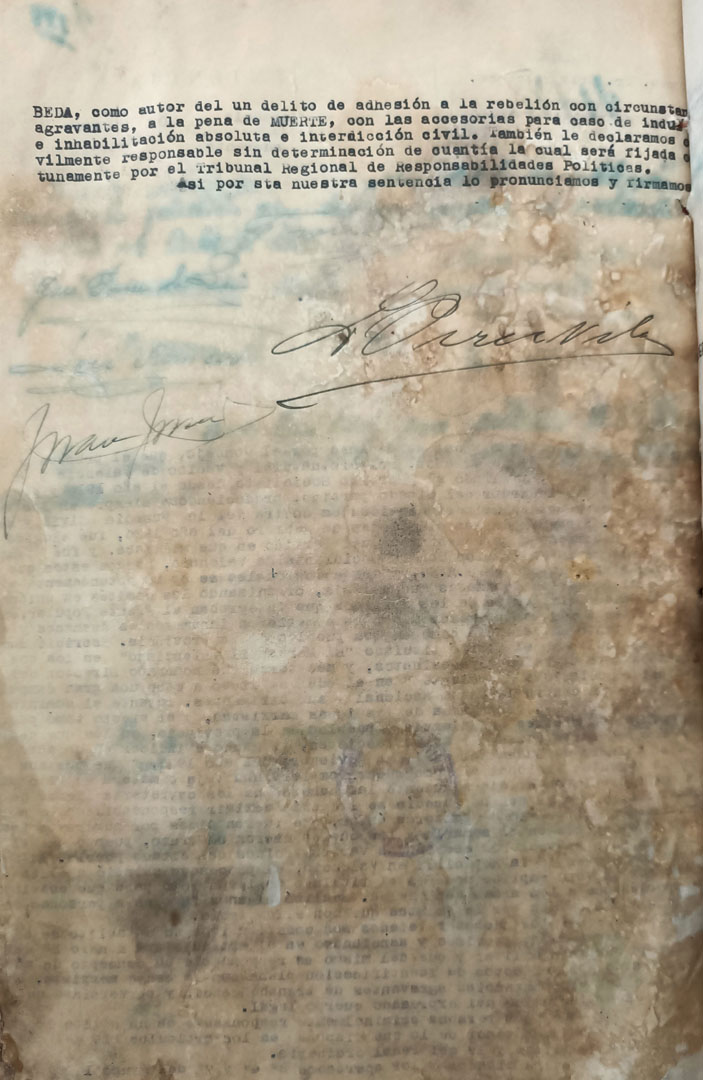

Differences?

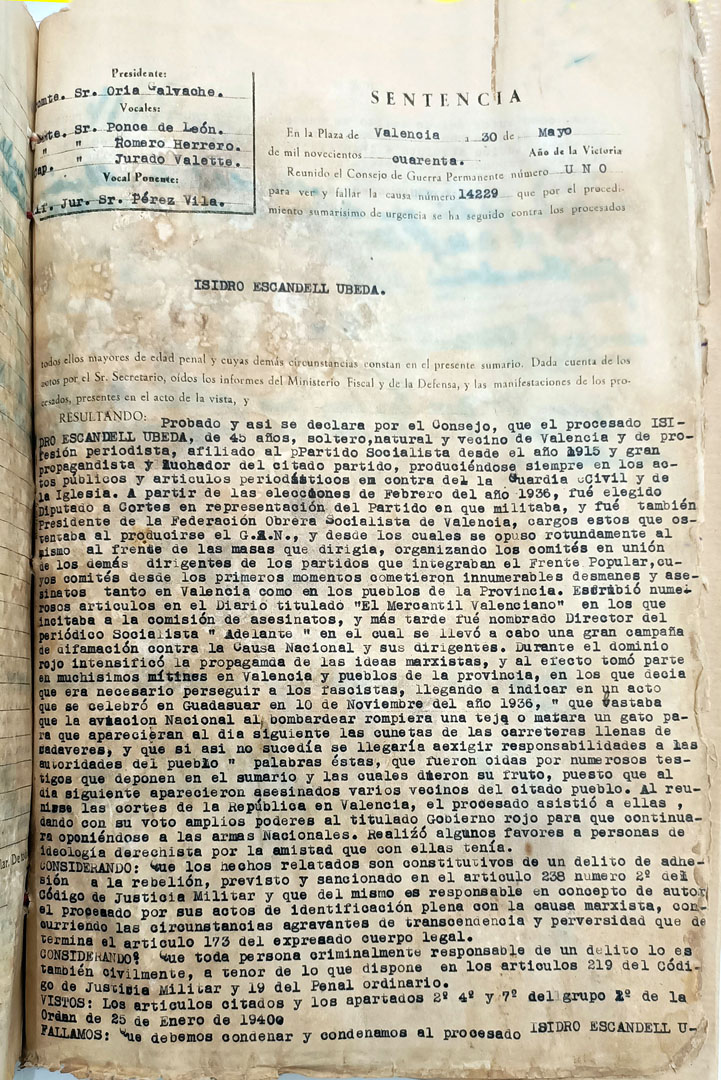

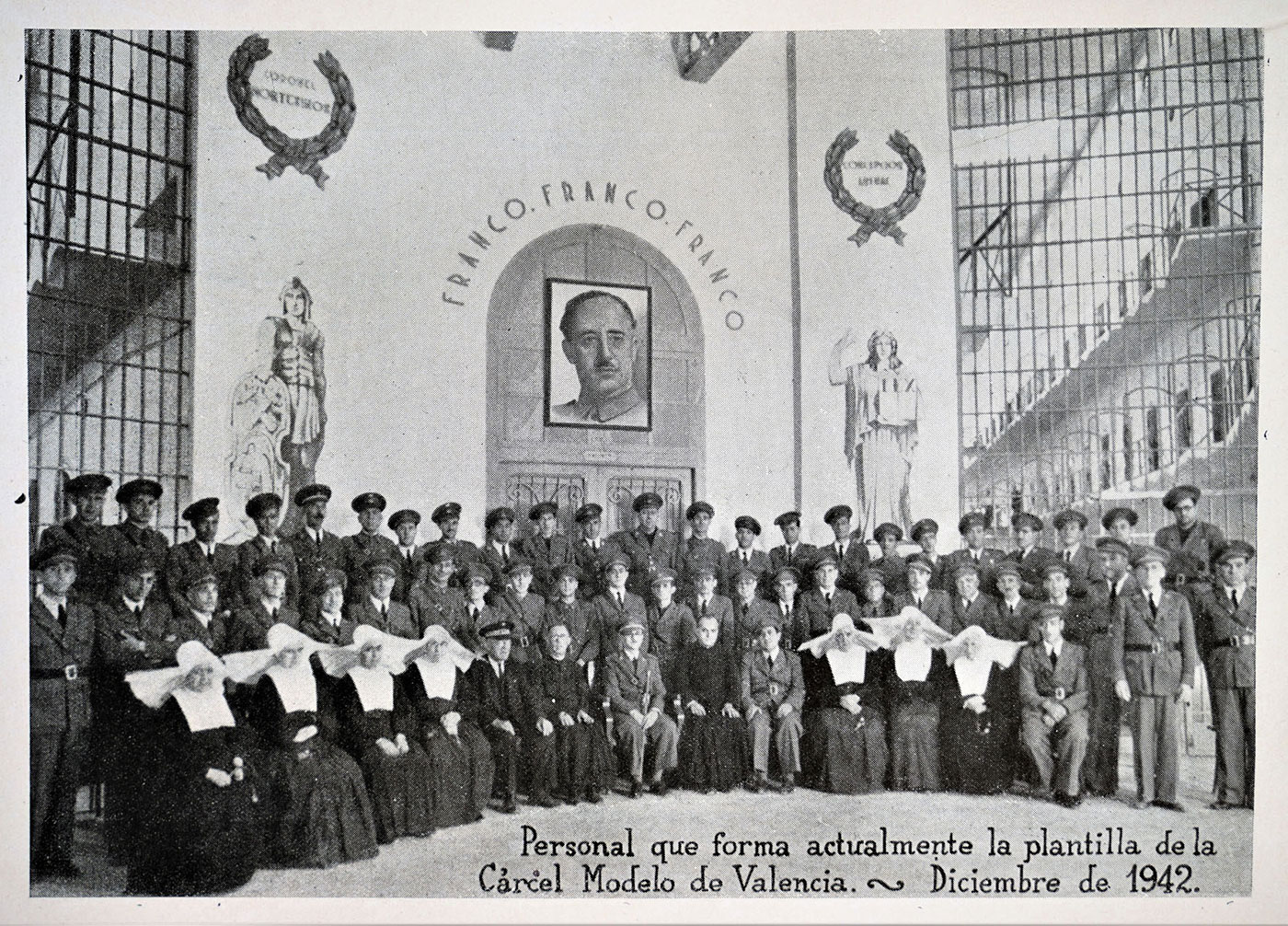

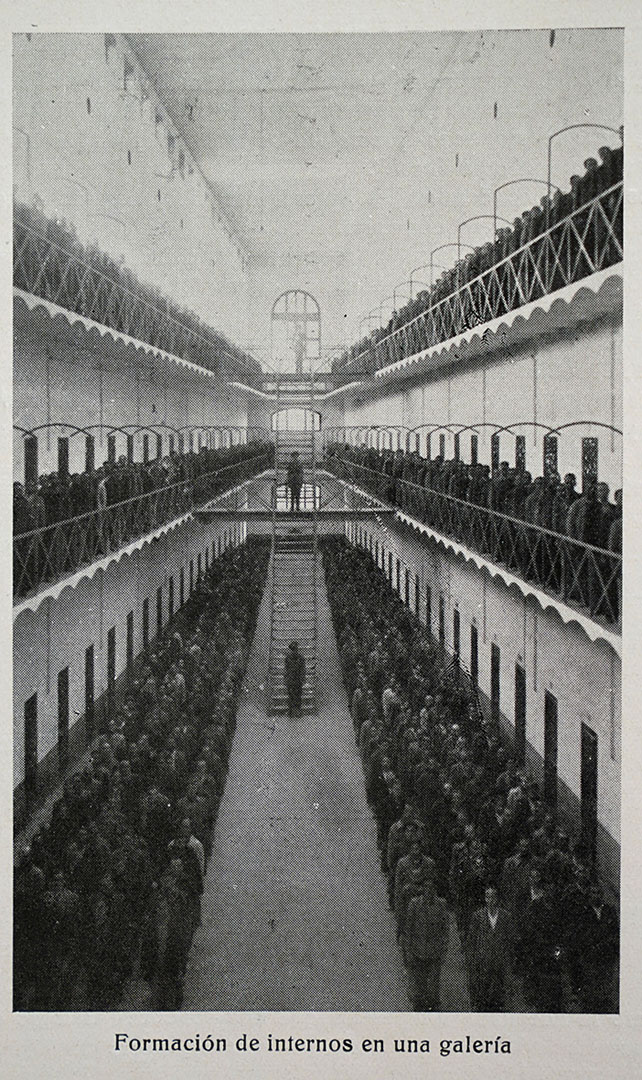

Executions were not continuous, and the Republican institutions, unlike their Francoist counterparts, gradually restricted summary proceedings until they were abolished.

After Franco’s victory and the imposition of the dictatorship, victims of the Republican rearguard were exhumed, identified, and buried with public honours.