Crimes were committed here, but it is also a site full of memories. At least 2,238 people were buried there in mass graves.

Paterna is a unique site: due to the extensive repression; the evident signs of institutionalised terror; the well-preserved biological state of the bodies buried there, and the fight by families to recover their memory.

According to research by Gavarda, in the entire territory of Valencia, 4,714 people were murdered from 3 April 1939 until late 1956.

Non-existent rights to a defence, trials that were a sham. The bureaucratisation of terror, the institutionalisation of repression. From recruitment centres to El Terrer firing line.

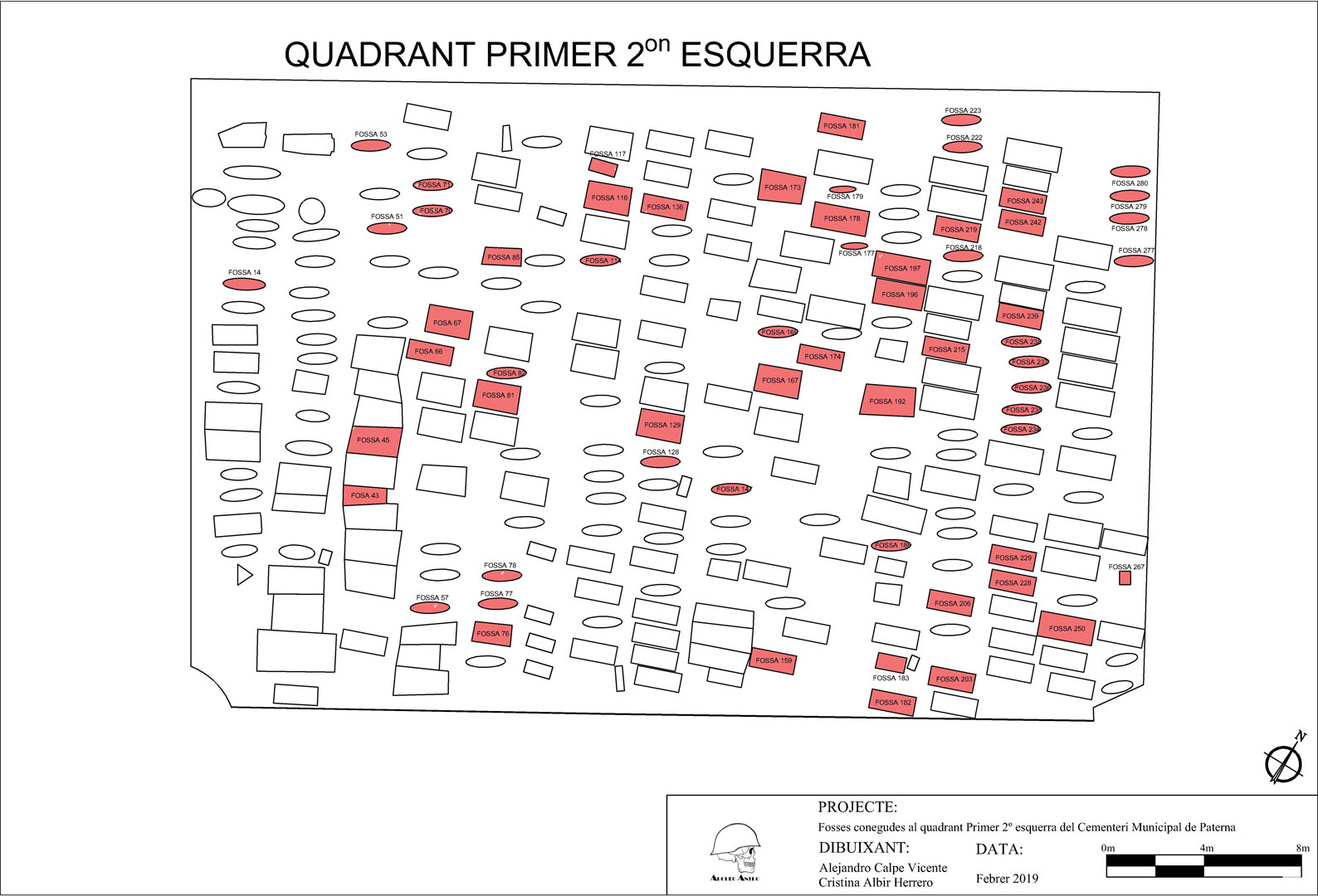

155 mass graves documented.

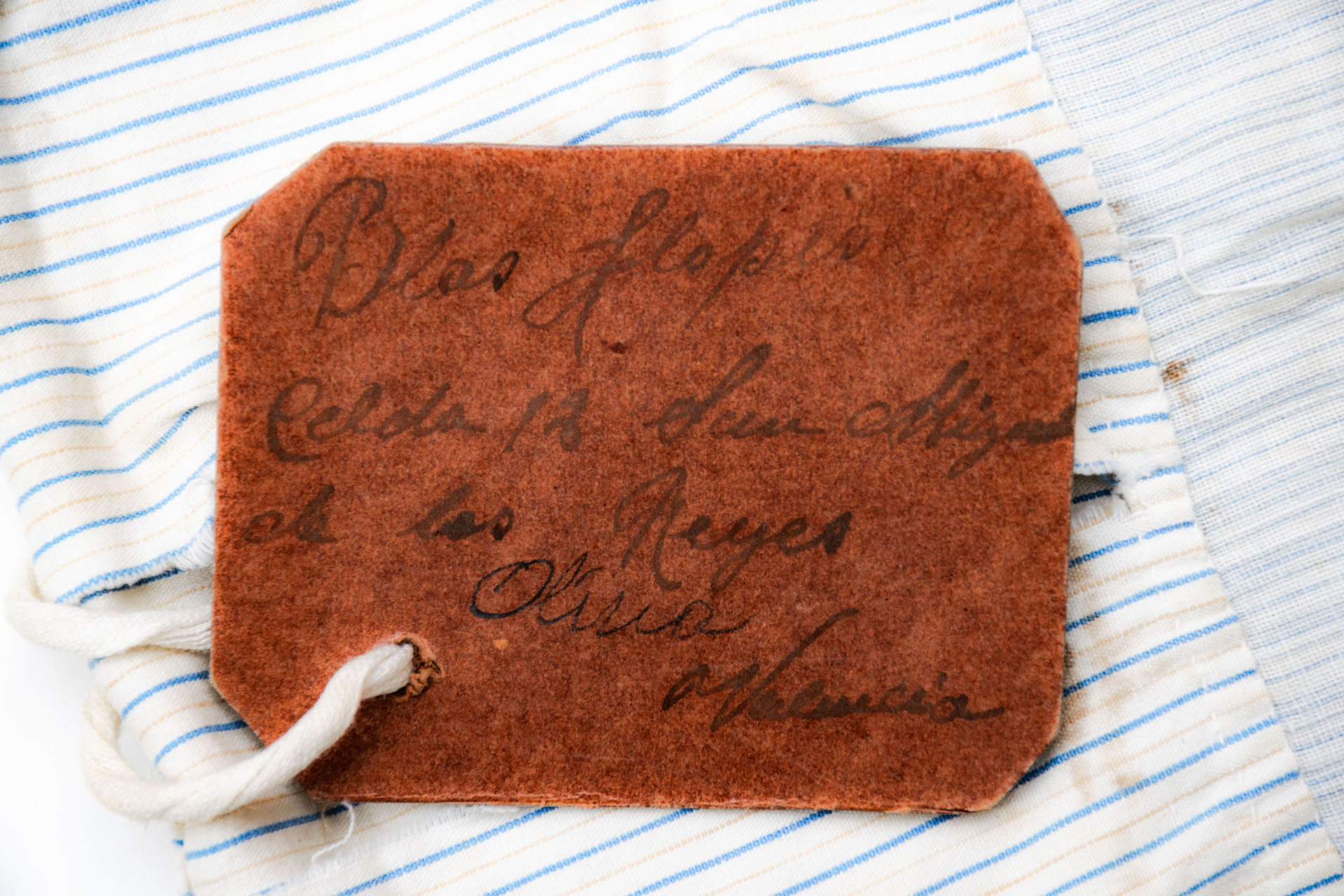

Mass graves signal a direct link to the past. Objects appear there that are reliable clues about part of the victims’ lives, everyday memories with details about the people murdered. They are therefore all essential for identifying the individuals found there and serve as conclusive evidence of the crimes.

Clothing is one of the most important tools when it comes to identifying victims, but also when determining their social class or profession. The type of footwear was a defining factor, since there was a stark contrast between social classes. Not all could afford leather ankle boots or army boots, and most made do with espadrilles finished off with pieces of rubber or repurposed tyre. In the photo: Valencian espadrilles typical of farmworkers.

Mass graves provide direct contact with a method of extermination, while the objects – such as the ropes found alongside the bodies – reveal the mechanisms of subjugation used by the oppressors, who bound their victims to prevent them from defending themselves.

Utensils provide clues about the identity of the people who disappeared. Moreover, the effects of “saponification” as evidenced in Paterna cemetery, have enabled objects to be recovered in good condition.

Clothing belonging to a victim, with holes that could very well indicate the entry point of the bullets that killed them.

Mass graves enable numerous objects to be recovered linked to the subject’s life, such as keys, coins, broken pencils so that several prisoners could use them, lighters, or cigarette cases.

Objects that speak of a crime. A rope used to tie a victim’s hands and bullets removed from the human remains that were found. Forensic archaeology uses classic archaeological techniques in the search, location and exhumation of human remains revealing violence. Exhumation is carried out within a judicial framework essential for clarifying the circumstances of the death.